Professor Emily Jane McTavish and colleagues at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology have mapped the evolution of every known bird species.

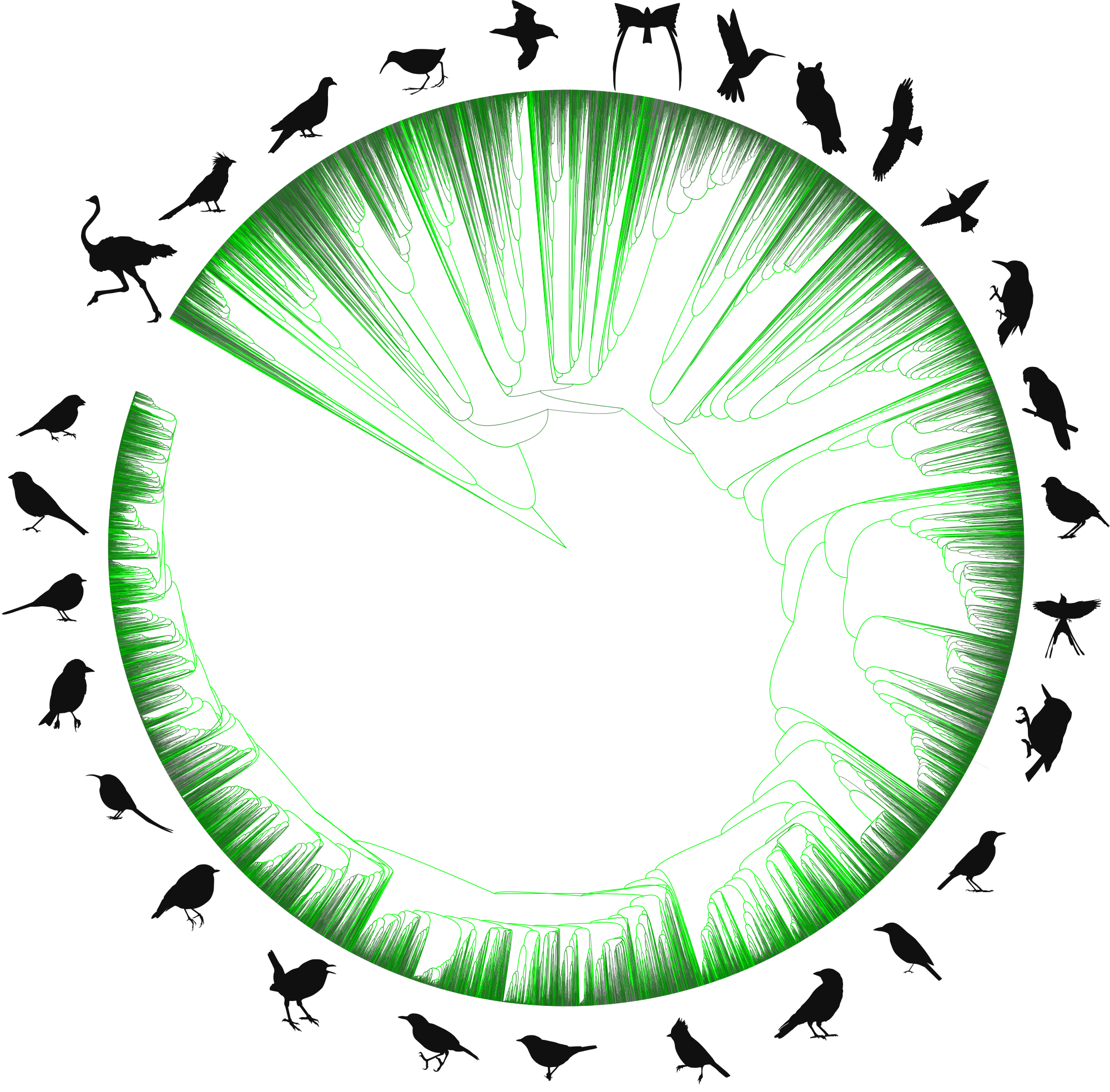

They created a complete evolutionary tree of bird species by combining data on 9,239 species published in nearly 300 studies between 1990 and 2024 and additional curated data on another 1,000 species. The resulting database can easily be shared and updated as additional studies are published.

“People love birds, and a lot of people work on birds. People publish scientific papers about birds’ evolutionary relationships all the time,” McTavish said. “We synthesized all the data to have unified information all in one place.”

The researchers detailed how they created this novel evolutionary map in a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Science (PNAS). The authors wrote that the synthesis tree could help inform various research questions about bird evolution and ecology. In addition, the methods used to produce the tree could be used for other types of animals and plants.

The project started about four years ago when Eliot Miller, then with the Cornell lab, reached out to McTavish, who has been working on software for the Open Tree of Life (OpenTree) project for about a decade.

“Many dozens of bird phylogenies (studies of evolutionary histories using genetics) get published every year, yet their findings — with implications for everything from taxonomy to our understanding of ancestral characters — aren’t necessarily being used for downstream research,” Miller said. “Our project should help to close this research loop so that these studies and their findings are better incorporated into follow-up research.”

McTavish said that though she hadn’t met Miller before he asked her to collaborate, this project dovetailed perfectly with her continuing work.

“Eliot is really into birds, and the lab is full of bird experts, and they also develop birding apps such as Merlin and Ebird, so that was their side of it, and I've been working on this software to combine evolutionary trees, so that was my side of it,” she explained.

OpenTree is a collaborative project that brings together evolutionary biologists and taxonomy experts to build an accurate, comprehensive evolutionary tree that describes how every named species on Earth is related to every other. It works on a wiki-like model, allowing users to manually upload data to update the tree's evolutionary relationships.

McTavish explained that as new understandings of relationships emerge, users can add that information to the Tree of Life to ensure that it reflects the most current understanding of evolutionary relationships between species.

With more than 2.5 million species now represented in the Open Tree of Life — and new data constantly streaming in thanks to advances in genome sequencing — McTavish, a biologist with the Department of Life and Environmental Sciences in the School of Natural Sciences, and a collaborator have been writing software that automatically updates the tree as data emerges.

She said the bird species synthesis fills one more gap in the Open Tree.

Like the new study, the Open Tree project is supported by funding from the National Science Foundation, which McTavish said has been crucial for establishing collaborations, gathering data from hundreds of published authors, and sharing information across disciplines and institutions.

“This open science and collaborative environment really made this possible,” she said.