It was only after graduate school, while working as a professor, that James Zimmerman realized something had been missing from his education.

Trained as a nuclear scientist, Zimmerman was well-prepared for a life in the laboratory, where success is measured in data and discovery. Though confident in his ability to understand the atom, Zimmerman was less certain of his ability to lead a classroom.

That’s because graduate school readied him — as it does with most aspiring academics — for a research career, largely glossing over the fact that teaching is an integral component of academic life.

“The challenge most faculty face is that when they get their Ph.D.s, they only learn to be an expert in their discipline,” Zimmerman said. “Depending on what institution they attend, they may have opportunities to seek out best practices in teaching, but that occurs quite rarely and is frankly up to the individual learner.”

Unsure whether his own instructional efforts were effective, Zimmerman pored through the educational literature to find out.

“While teaching at the university level, I was implementing active learning techniques with promising results,” Zimmerman said. “But nobody seemed to know how or why they worked.”

The following article appeared in the October 2017 issue of Merced Monthly, an e-newsletter for the UC Merced campus community and friends. To subscribe, click here.

A Focus on Teaching and Learning

Zimmerman’s hunt for ways to assess his own teaching grew to be all-consuming. He eventually left the lab to focus on education research full time. This led him to UC Merced, where he now serves as Associate Vice Provost for Teaching and Learning and director of the Center for Engaged Teaching and Learning (CETL).

CETL helps the university’s instructors, many of whom are confronted with the same challenges Zimmerman faced years earlier, engage in educational research and implement data-driven approaches to maximize student learning.

“The basic premise of CETL is to create a culture on campus where faculty view student learning as a valid object of scholarly inquiry,” Zimmerman said.

CETL provides instructors and students with resources that help them identify the best ways to transform the classroom into a space where comprehension, rather than mere delivery of material, is the primary goal. CETL is not in the business of providing generic “tips and tricks” that do little to foster an engaged learning environment. Under the guidance of Associate Director Anali Makoui, they help instructors assess their current classroom strategies and evaluate the usefulness of new approaches.

“When instructors want help figuring out if their instruction is effective, they can turn to us,” said Adriana Signorini, coordinator of CETL’s Educational Assessment Unit. “We don’t tell anyone what to do in the classroom. Everything we provide is to assess effectiveness, not teach faculty how to teach. We provide support if they have questions about educational research, and we discuss different evidence-based teaching practices with them.”

CETL can help instructors gather student-specific data that informs classroom decisions. This is especially important at UC Merced, where 71 percent of students are first-generation and 65 percent grew up in homes that spoke a language other than English. Assembling student demographic information before a course begins allows instructors to target students’ strengths and weaknesses.

“Our students bring extraordinary strengths to campus, but many are unfamiliar with the unspoken aspects of academic culture,” Zimmerman said. “It’s our job to help instructors learn to navigate that with their students.”

Student Input Actively Sought, Heard

CETL assesses student satisfaction throughout the semester, allowing faculty to make mid-term course corrections. CETL even holds workshops to train students on how to complete end-of-semester course evaluations to provide the most useful feedback possible.

“The new paradigm of education is to involve students,” Signorini said. “We’re teaching them, so we need to include their perspective. Student voices need to be taken into account in curriculum development”

The information CETL gathers can inform everything from minor corrections, like syllabus rewrites, to large-scale changes like overhauling the curriculum for a whole major. CETL even helps faculty draft grant proposals.

Many federally-funded grants, which ostensibly support basic scientific research, require researchers to include an educational outreach component accompanied by a list of ways to assess its effectiveness.

Applied Mathematics Professor Noemi Petra credits Signorini and CETL with helping her design the education portion of her application for the National Science Foundation CAREER award. Petra received the grant, the most prestigious the NSF awards to junior faculty, in September.

“I was so fortunate when Adriana and CETL came into the picture,” Petra said.

But this wasn’t Petra’s first experience with CETL. She’s worked with the center continuously since arriving at UC Merced.

“I was lucky my colleagues mentioned them to me when I first got here,” Petra said. “Now I invite them to every single class every semester. Their feedback is eye opening.”

When instructors want help figuring out if their instruction is effective, they can turn to us.

Specialized Teaching for Unique Students

CETL continues to expand its offerings. One of their newest initiatives is the Faculty Academy on Teaching First-Year Students. The academy solicits proposals from instructors eager to better engage UC Merced’s unique cohort of first-year students.

Somnath Sinha, a lecturer in the School of Natural Sciences, was one of the academy’s inaugural participants. As a member of Calteach, Sinha prepares UC Merced undergraduates to be tomorrow’s K-12 STEM teachers.

“Teaching aspiring teachers has added responsibilities,” Sinha said. “I was very concerned about my teaching, and I wanted to improve my teaching based on research.”

When Sinha saw a flyer for the academy in Fall 2016, he was intrigued. After participating, much like Petra, he felt the experience was invaluable.

“They don’t just give tips, they provide customized research for each faculty member,” Sinha said. “Their advice is specific to you.”

Going forward, Zimmerman envisions continued growth for CETL. Though he wants CETL’s English Language Institute to continue studying how students who speak English as a second language adapt to academia, he also wants to encourage the institute to identify communication strategies that encourage classroom participation from ESL students while also noting those that erode trust.

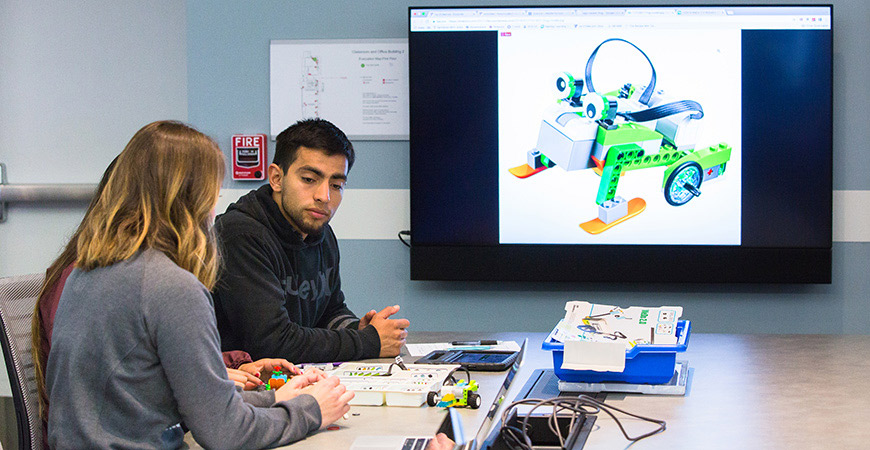

Zimmerman also sees educational technology as a top priority. In collaboration with the office of Academic and Emerging Technology (AET), CETL recently launched the campus’s first Technology Enabled Active Learning (TEAL) lab, a high-tech classroom with an unusual layout that’s designed to promote active learning. The center is also using funds from the UC Office of the President’s Innovative Learning Technology Initiative to enlist faculty to help determine which courses work best in an online environment versus those that require in-person participation.

And as the campus grows through the Merced 2020 Project, Zimmerman also wants to make it easier for faculty to access CETL’s many resources.

“We hope to create a faculty learning hub centrally located on campus,” Zimmerman said. “We want faculty to know they can come to one place and have access to all of our offerings.”