UC Merced graduate students and their professor have collaborated on a sound-based documentary that meditates on the wars that traumatize everyday lives and how we can push back with determination, compassion and love.

“After the War: an Ultrasonic Meditation” was made in collaboration with the University of California Humanities Research Institute. UCHRI facilitates experimental, interdisciplinary humanities scholarship through partnerships, research initiatives and competitive grants.

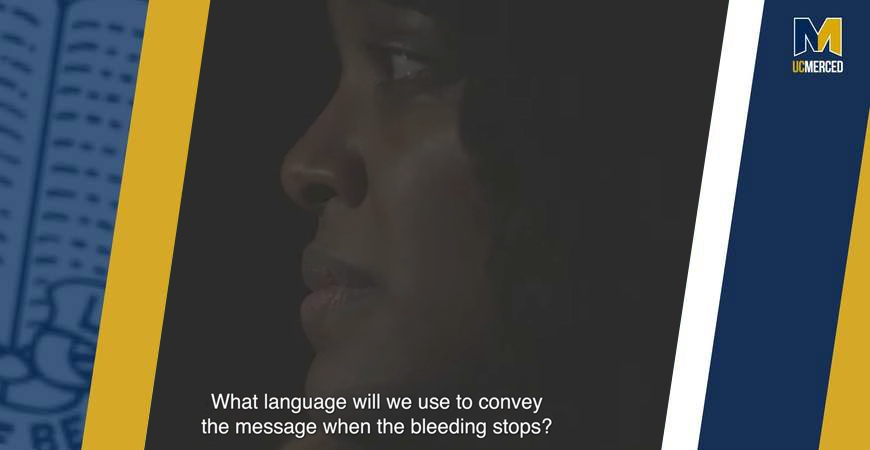

“After the War” was created and composed by Professor Yehuda Sharim, with contributions from Merced community members and Interdisciplinary Humanities graduate students Chiquitha Aminsalehi, Shiraz Noorani and Bethany Padron. The project combines original music, poetry, spoken words and video.

“This sonic documentary is not about a utopic future after the war, but an invitation and provocation to return home, come to terms with the harm and injuries we commit and carry and turn internal spite into unflinching determination and tenderness in a world obsessed with calamities and rancor,” Sharim wrote for the UCHRI presentation.

Sharim said the seeds for “After the War” were planted last year, when he worked on how to show the ways people find a path to healing amid violence that is normalized and injustices that are treated like casual events.

Aminsalehi and Padron, after joining the project, met at the UC Merced Library each week to exchange ideas. They began to visualize the effects of war on their ancestors and on generations to come.

“We wanted to honor those who lost their lives too soon in a constant struggle against greed, consumption, domination and anguish,” Aminsalehi said.

They wrote some poetry stanzas separately, then read them to each other.

“When we finished, our eyes smiled,” she said. “We knew we had created something that would last and pay homage to what it meant to convene and reflect on what our souls sought to say.”

They had discussed the project’s broad strokes in a conversation with Sharim months earlier. With the words in hand, “After the War” moved forward. Through his community work, Sharim composed the soundscape music. The students interpreted their words in front of the camera.

“Personal experiences reflected in this project have lingering touches of surviving,” Padron said. “Because the wounds have been deep, I wear red lipstick in the filming as a reminder that I am alive.”

For Noorani, a native of Afghanistan, war was — is — all too real. “I grew up where every morning's newsbreak brought reports of killings, injuries or explosions,” he said. A close friend was among two dozen people killed in an attack by Islamic State gunmen at Kabul University in 2020.

“War may end in a specific time and place, but its aftermath stays within us,” Noorani said. “It shapes identities and beliefs in ways we may not anticipate. The battles we fight in ourselves — the grief, the loss, the search for meaning — stay long after the last gunshot is fired.”